During their time training, Kala enjoyed a relatively worry-free experience. Phase one and phase two were completed and they were excited to move onto their first posting.

Kala settled into their first posting quite comfortably. Kala was often working unsupervised in a specialist role, so there were little concerns or issues about their identity through this initial period. They had questioned their sexuality and gender on a number of occasions but had not yet come to terms with who they were.

“I wondered if I was gay at the time, I remember seeing Boy George on TV and being fascinated by their androgyny.”

Around two years into their service, rumours started to circulate. There was speculation around their sexuality and soon a steady wave of verbal abuse began by various service personnel they worked alongside. This also escalated to physical assault and at one point a group of other service personnel held them underwater until they nearly drowned.

“Comments were made directly to me, or to others in my presence, suggesting I was gay, concealed as jokes. This progressed to slurs. At work. At breaks. This led me to be socially isolated after work. Eventually, I was assaulted at work by a team member.”

“I believe that I represent a part of the veteran’s community that many others think is what is ruining the armed forces, they hate the diversity and inclusion side of the armed forces.”

These experiences continued, impacting Kala’s potential career progression. Some fellow personnel attempted to expose them and their sexuality. This resulted in a number of disciplinaries which could have been avoided and impacted their ability to gain promotion. This is likely to have led to the investigation that eventually resulted in dismissal.

“I was asked to leave the service with just three days’ notice, citing ‘services no longer required’. They had no evidence of my being pansexual or trans, but my divergent gender expression and mannerisms gave them all the reason they needed to cause me a lot of trouble.”

Kala’s service in the military came to an end in 1994. They were still very confused about their sexuality and gender identity while suffering from a number of lasting impacts. They developed PTSD and attempted suicide. For a long time they carried a lot of shame, hiding their military past while struggling to create and maintain meaningful relationships.

“10 years after discharge, I tried to eventually seek support, but I was wrongly diagnosed with borderline personality disorder when I actually had untreated PTSD. This developed into C-PTSD. Finally, after 30 years I am now receiving the support I need for C-PTSD.”

Life since discharge from the armed forces has been difficult, they have struggled to hold down employment and ended up homeless for a time. The representation of queer veterans in their immediate community is low, with some of those who access their local services remaining opposed to the lifestyle and identity of LGBTQ+ people making it easy to become isolated.

“I believe that I represent a part of the veteran’s community that many others think is what is ruining the armed forces, they hate the diversity and inclusion side of the armed forces.”

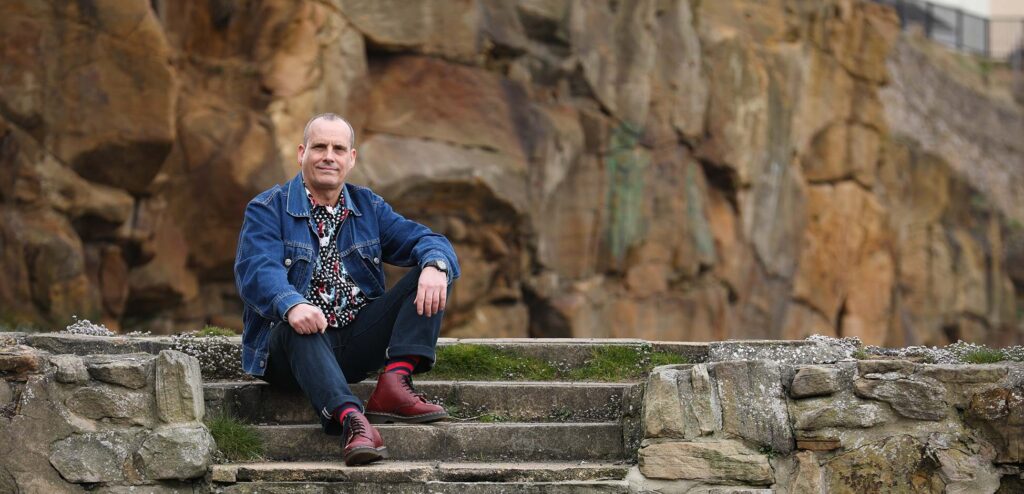

Kala now lives in veteran’s accommodation by the seafront and finds comfort by spending their time painting and looking after their two cats. A lot of Kala’s artwork reflects their feelings towards life and how it has treated them; the highs and the lows. Some of their artwork has been exhibited at LGBTQ+ events in the city of Newcastle. They live quietly, continuing to build relationships with their immediate family, but remain aware of external feelings towards them in the veteran community.